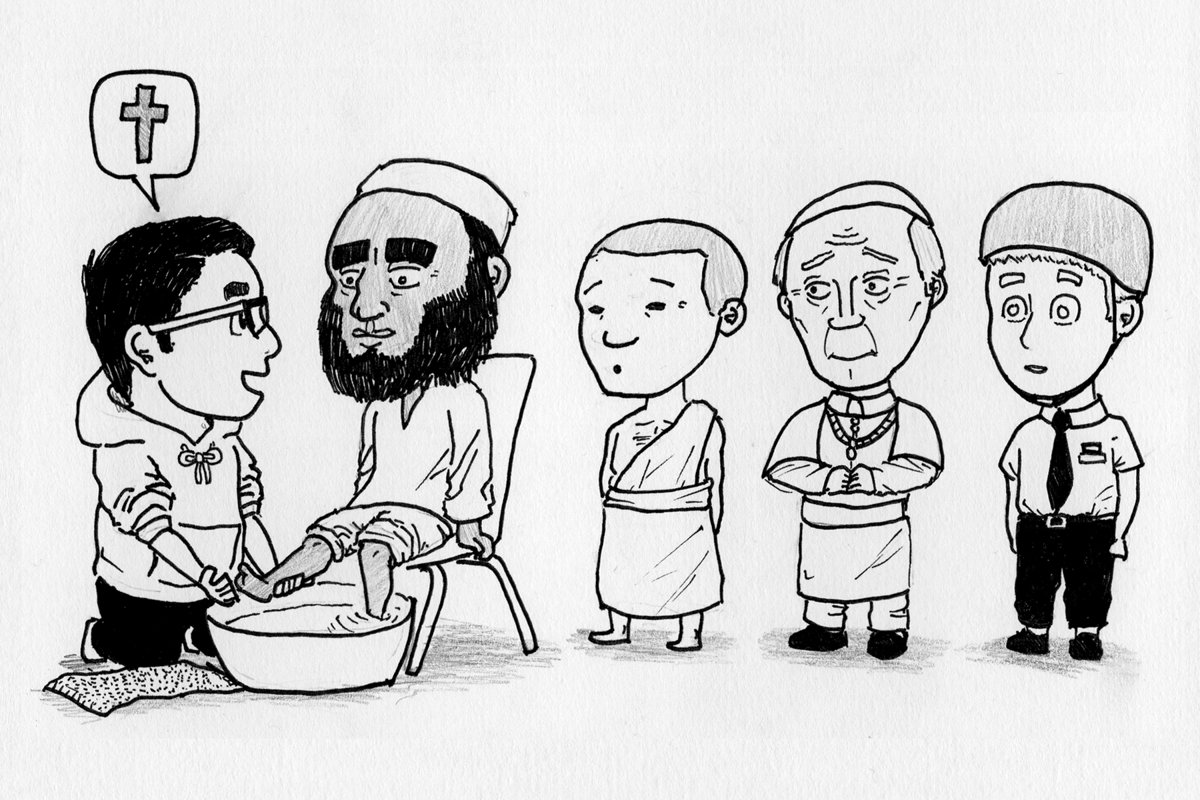

Illustration by David Rhee/Chime

A child dies at home.

The police are called about a child not breathing and rush to the residence. The exterior of the home looks much like others in the suburban-like neighborhood where homes are close. From the outside view, there is little evidence that all is not well with this family.

That all changed when the police open the front door to expose rooms full of garbage and mold and find an six-month-old child dead inside. The medical examiner’s report attributes the death of the youngest member of the nine-child family to the conditions within the home.

Neighbors gathered in the street are interviewed by local news media. They say that they called the police about suspected problems with the family several times. One neighbor says she “knew” no one would do anything until one of the children “passes away.”

Strangely and tragically, that’s exactly what happened.

What seems to be in play here is what is called a self-fulfilling prophesy, which is an expectation that brings about its own fulfillment. If you believe something to be true, you’ll act as if it were true.

A self-fulfilling prophesy can influence behavior (positive or negative) in a way that ushers the belief into reality. Essentially, it can shape action that leads to those expectations being realized.

Expecting something to go wrong, you might fail to take steps that could turn things around.

“These expectations can play a part in stereotypes, racism, and discrimination,” according to Kendra Cherry, a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist and psychology educator. “Expecting the worst brings out the worst.”

Whether or not the real-life psychological effect of self-fulfilling prophecy was a factor in the death of this child is conjecture, since the truth will only be revealed as much as those involved are interested in revealing it. One thing is for sure, however: The people who knew or suspected that this child was in danger and failed to take action (other than making calls to authorities), will feel the weight of their inactivity for a long time and maybe for the rest of their lives, as would any of us, under similar circumstances.

So many questions. Did any neighbor go inside the house and see the severe unhealthy conditions? Did any neighbor offer to help if they knew the dangers inside? Was assistance offered but rejected by the adults living in the house? Did any neighbors befriend the family?

This incident – involving actual neighbors – brings much clarity to Jesus’ words written in Matthew 22:36-37. “And one of them, a lawyer, asked him a question to test him. “Teacher, which commandment in the law is the greatest?” He said to him, “‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.”

A commandment to love? This doesn’t seem like something you can or should command. How can you make or require someone to love; whether God, another human or, really, anything?

But this is Jesus (Emmanuel – God with us) saying this, so it has to be right and true. Understanding comes by looking at the original language used in Matthew, which is Greek.

The word “love” at the center of this Bible passage is a translation of the Greek word “agape.” Knowing this, it is easier to understand why Jesus would issue a command to us to “love” God and each other. This is because the Greek word agape doesn’t describe a feeling, especially a mushy feeling.

Rather, it describes a God-created force that is felt in some way or form by every entity in the universe from atoms up to entire societies, according to biblical scholar Arie Uittenbogaard, an Abarim Publications writer. So, Matthew was not as much commanding us to generate a personal feeling for God, ourselves, and others but highlighting the concept that we are created with a natural “love” force that compels us into action to help others.

Agape is God’s love language. It isn’t something we choose to feel, it is established by God, into every inch of his creation. Agape love is something we will do – just as Jesus commanded – naturally, unless we choose not to. Doing or being better for our “neighbor” is about believing in, and saying “yes” to our God-created design. We were made for this!